Очерк о капитане Эвери публикуется с любезного разрешения его автора, американской писательницы Синди Вэллар, владелицы и ведущей сайта “Pirates and Privateers: The History of Maritime Piracy”

Copyright © 2006 Cindy Vallar

Known as Henry Avery, John Avery, Long Ben, and Captain Benjamin Bridgeman, Henry Every’s beginning and ending remains cloaked in mystery. During the brief span of time in which he captained a pirate ship, however, he became a legend in his own time.

Little is known about Henry Every until 1689, although he may have been the son of John and Anne Evarie (spelling uncertain) of Newton Ferrers, a village located a short distance from Plymouth, England. Daniel Defoe in the “King of Pirates” claimed Every’s birth year as 1653, although another source says 1659. In March 1689, however, he was a midshipman in the English Royal Navy aboard HMS Ruppert. Four months later, he was promoted to chief mate of the sixty-four-gun vessel under the command of Captain Francis Wheeler. When Wheeler became captain of HMS Albemarle in June of the following year, Every accompanied him aboard the ninety-gun ship. In August, he was discharged from the navy.

The next surviving documentary record of Every lists him as a crewmember of the Charles II in 1693. He became the vessel’s first mate in early 1694. The armed frigate was one of several vessels that comprised a flotilla hired to raid Spanish colonies or that the Spanish hired to attack French smugglers based on Martinique. The flotilla’s first port of call was La Coruña. The unpaid men languished there until Every led a mutiny on 7 May and seized the ship. Some accounts say Captain Gibson, who loved to drink, went ashore with some of the crew to a tavern, which provided Every with the ideal moment to take control. Other accounts say the captain was in a drunken stupor in his cabin and didn’t learn about the mutiny until the next day when Every said, “I am captain of this ship now. I am bound to Madagascar, with the design of making my own fortune, and that of all the brave fellows joined with me.” (Cordingly, 21) Gibson and up to sixteen others were set adrift in a boat near Africa.

At the time Every became a pirate, he was probably in his forties. He was described as being “middle-sized, inclinable to be fat and of a jolly complexion.” A good navigator and sailor, he was “daring and good tempered, but insolent and uneasy at times, and always unforgiving if at any time imposed upon. His manner of living was imprinted in his face, and his profession might easily be told from it. His knowledge of his profession was great, being founded on a strong natural judgement, and sufficient experience advanced by incessant application to mathematics. He still had many principles of morality which many subjects of the King have experienced.” (Botting, 80) He garnered the respect of his men and other pirates, so much so that they eventually put him in overall command of six pirate ships.

One of the pirates’ first tasks was to rename the Charles II. Then they adapted the Fancy to suit their needs. A captain of an East Indiaman that tried to capture Every and his ship off the island of Johanna said, “he was too nimble for them by much, having taken down a great deale of his upper work and made her exceeding snug, which advantage being added to her well sailing before causes her to saile so hard that she fears not who follows her.” (Earle, 126)

Every plundered three English ships off the Cape Verde Islands, then took two Danish vessels near Principe on the west coast of Africa. At one point the Fancy put in at Johanna, and Every left a note behind with instructions to deliver it to the first English ship that docked after he left.

To All English Commanders.

Let this satisfy that I was riding here at this instant in the ship Fancy, man of war, formerly the Charles of the Spanish Expedition who departed from La Coruña 7th May 1694, being then and now a ship of 46 guns, 150 men and bound to seek our fortunes. I have never as yet wronged any English or Dutch, or ever intend whilst I am commander. [a lie] Wherefore as I commonly speak with all ships I desire whoever comes to the perusal of this to take this signal, that if you or any whom you may inform are desirous to know what we are at a distance, then make your ancient [ship’s flag] up in a ball or bundle and hoist him at the mizen peak, the mizen being furled. I shall answer with the same, and never molest you, for my men are hungry, stout and resolute, and should they exceed my desire I cannot help myself. As yet an Englishman’s friend,

At Johanna, 18th February 1695

Henry Every (Botting, 82)

After a brief stop at Madagascar to replenish supplies and wait for suitable weather, Every set sail for Perim Island in the Red Sea with the intent of intercepting vessels carrying pilgrims from Mecca to India. Once Every arrived there, several other pirate vessels joined them: Pearl (Captain William May), Portsmouth Adventure (Joseph Farrell), Amity (Thomas Tew), Dolphin (William Want), and Susana (Thomas Wake). These pirate captains and their men agreed that Henry Every should lead them in their hunt for treasure.

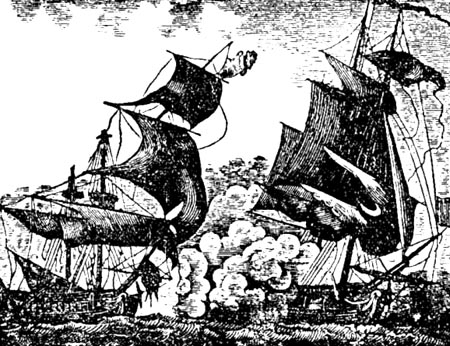

On 8 September 1695, the pirate fleet sighted two vessels. The pirates’ first objective was to capture the Fateh Mahmamadi, which carried gold and silver valued at more than £50,000. She was an unarmed merchantship owned by Abd-ul Ghafur.

The second ship proved more significant, for it was the Gang-i-Sawai (Ganj-i-Saway or Gunsway), one of the Great Moghul’s largest ships. Armed with forty to eighty great guns and four hundred musketeers, she was captained by Muhammed Ibrahim. Although the forty-six gun Fancy was no match for the larger ship, Every didn’t hesitate to attack. Luck was with the pirates, for one of their shots toppled the mainmast and one of the Gang-i-Sawai’s guns exploded, killing or wounding a number of sailors. She didn’t surrender, though, and the battle raged for two hours. As many as twenty pirates lost their lives, including Thomas Tew, a successful pirate who had retired after amassing a fortune that exceeded £100,000 but opted to go on one more adventure. “[A] Shot carry’d away the Rim of Tew’s Belly, who held his Bowels with his hands some small Space; when he dropp’d, it struck such a Terror in his Men, that they suffered themselves to be taken.” (Defoe, 75)

Among the captured passengers were men and women, and possibly a daughter of the Great Moghul. While Every claimed no harm befell the women, one pirate later confessed at his trial that the pirates committed “horrid barbarities.” (Every, however, may not have participated in the debauchery.) Khafi Khan, an Indian historian of the time but who wasn’t present at the attack, wrote, “When they [the pirates] had laden their ship, they brought the royal ship to shore near one of their settlements, and busied themselves for a week searching for plunder, stripping the men, and dishonouring the women, both old and young. They then left the ship, carrying off the men. Several honourable women, when they found an opportunity, threw themselves into the sea, to preserve their chastity, and some others killed themselves with knives and daggers.” (Rogozinski, 86) What eventually became of the women who survived is unknown.

The Gang-i-Sawai was laden with large amounts of gold, silver, and jewels, and a gold-trimmed saddle set with rubies. The Great Moghul set the take at £600,000, but the East India Company estimated the loss at £325,000. Assuming the Great Moghul’s estimate was correct, Angus Konstam, author of “The History of Pirates” (1999), computed the present-day value of the treasure at about $105,000,000. Each pirate who received a full share garnered £1,000 or $176,000 today. Boys under eighteen received £50 each, the amount of money a seventeenth-century merchant sailor earned in his entire life. Jan Rogozinski, in his book “Honor Among Thieves”, used the East India Company’s valuation to compute the booty’s worth in 2000: £37,000,000 or $188,000,000.

When the Great Moghul learned of the attack, he vented his outrage on the English and the East India Company, threatening to kick all of them out of India. Intricate diplomacy and assurances that the pirates would be brought to justice eventually repaired the damage that this single piratical attack had wrought. In July 1696, the Privy Council condemned Henry Every and his crew, and offered a £500 reward for their capture. The East India Company added another £500 to the reward. Henry Every was excluded from receiving any pardon as a result of the Acts of Grace.

With the riches secured from these two captures, Every chose to retire. The Fancy sailed for the Caribbean after stopping at Réunion to take on a consignment of ninety slaves. She also stopped at Sao Tomé, a Portuguese island, where Every forged a Bill of Exchange drawn on the Bank of Aldgate Pump, witnessed by John-a-Noakes, and signed by Timothy Tugmutton and Simon Whifflepin. (This act is equivalent to bouncing a check today.) Every’s next port of call was the Danish island of Saint Thomas where the pirates sold their booty. Pére Labat, a Jesuit priest, wrote, “A roll of muslin embroidered with gold could be obtained for only 20 sols and the rest of the cargo in proportion.” (Botting, 85)

Every and his crew arrived at Royal Island off Eleuthera, fifty miles from New Providence in the Bahamas, in late April 1696. To gain the governor’s goodwill, they gave him their ship, gold, and ivory tusks valued at £1,000. The pirates hoped to gain pardons, but since Governor Nicholas Trott wasn’t a royal governor, he lacked the power to grant them. They sailed for Jamaica in hopes of obtaining the pardons from Jamaican Governor William Beeston. On 15 June, he wrote to the Council for Trade and Plantations in London, “They are arrived at Providence and have sent privately to me, to try if they could prevail with me to pardon them and let them come hither; and in order that I was told that it should be worth to me a great sum (i.e. £24,000), but that could not tempt me from my duty.” (Botting, 87)

As a result of Governor Beeston’s refusal, Every returned to the Bahamas where he and his men lived aboard the Fancy, even though they had given her to Governor Trott. Either purposely or through negligence, the ship was driven ashore in a gale. After salvaging her guns and whatever else they could, the pirates dispersed. Joseph Morris stayed in the Bahamas. Rumor says he went mad after losing much of his booty while gambling. Another pirate eventually married the daughter of Governor Markham of Pennsylvania. A shark off Jamaica claimed a third pirate.

Henry Every adopted the name of Benjamin Bridgeman and purchased a sloop. He and others sailed for the British Isles. The Westport sheriff in County Mayo arrested several in Ireland. John Dann, who quilted his gold into the lining of his jacket (£1,045 in half sovereigns and ten guineas), was captured in Rochester, England after a chambermaid discovered the weight of the jacket and told the mayor. Jewelers and goldsmiths in Bristol and London informed on others who attempted to sell their ill-gotten gems and foreign currency. In all, twenty-four of Every’s men were captured. Six were hanged. Most of the others were transported to Virginia as convict laborers.

Henry Every, however, was never caught. Once he landed at Dunfanaghy, thirty miles from Londonderry in County Donegal, Ireland, he disappeared. People reported sighting him in Scotland, Dublin, Exeter, Plymouth, and London, but these reports were never substantiated. Defoe claimed that rich merchants swindled Every of his treasure and he died a beggar in Bideford, England, “not being worth as much as would buy him a Coffin.” (Botting, 91) Although few people know of him today, the same wasn’t true then. In 1713, a new play opened at Drury Lane Theater. Charles Johnson (not the author of The General History of the Pyrates, but a second-rate dramatist) had written the play, which depicted Every as a brave outlaw. It played to audiences for several years before closing.

Copyright © 2006 Cindy Vallar

For more information, I suggest:

Botting, Douglas. The Pirates. Time-Life, 1978.

Cordingly, David. Under the Black Flag. Random House, 1995.

Defoe, Daniel. The General History of the Pyrates. Dover, 1999.

Earle, Peter. The Pirate Wars. St. Martin’s, 2003.

Johnson, Charles. The General History of the Pirates. Lyons Press, 1998.

Konstam, Angus. The History of Pirates. Lyons Press, 1999.

Marley, David F. Pirates and Privateers of the Americas. ABC Clio, 1994.

Pirates: Terror on the High Seas from the Caribbean to the South China Sea. Turner, 1996.

Rogozinski, Jan. Honor Among Thieves. Stackpole, 2000

|